Technology that captures, concentrates, and destroys PFAS can also help eliminate associated environmental, legal, and regulatory risks of ‘forever chemicals.’

Today’s textiles offer superior performance such as water and oil repellence, stain resistance, and flame retardancy. What has made it possible is a family of synthetic chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Known as “forever chemicals” because they don’t naturally degrade, PFAS can be found in the water, soil, and air — and human bodies — virtually everywhere in the world, even Antarctica.

Only about 40 PFAS compounds are currently regulated in the United States even though the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says there are more than 9,200 created since their introduction in the 1940s. There is direct evidence that PFAS negatively affect human health, including increased risk for various cancers, hormone disruption, weakened immunity, and reproductive problems.

The spotlight on PFAS pollution and the textile industry is global. As public awareness about the health risks of PFAS grows, so too does public demand for action.

The “forever chemicals” also harm the environment, especially in aquatic ecosystems downstream of discharges from industrial and wastewater treatment plants. These risks to the environment and human health are leading to reputational, legal, and regulatory liabilities for textile and related industries.

Textile Industry Singled Out as a PFAS Polluter

On Jan. 26, the Environmental Working Group (EWG) announced that it identified more than 1,500 U.S. textile mills that may be releasing “forever chemicals,” targeting the textile industry out of the 29,900 industrial sites in its analysis.

“PFAS exposure can cause serious health impacts at very low levels. It is a public health crisis that these chemicals can and may be dumped into the air and water downstream of textile mills and other industrial sites,” said David Andrews, a senior scientist at EWG.

EWG cited a report by Toxic-Free Future, which found evidence of PFAS in 72% of stain- and water-resistant home furnishings and clothing. The report followed the “toxic trail of pollution,” namely chemical production, product manufacturing, product use, and product disposal.

The spotlight on PFAS pollution and the textile industry is global. The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) published “Engaging the Textile Industry as a Key Sector in SAICM: A Review of PFAS as a Chemical Class in the Textile Sector” in 2021. Adopted by the First International Conference on Chemicals Management in 2006, the objective of the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) is to manage chemicals throughout their life cycle to minimize harm to the environment and human health.

The textile industry is one of SAICM’s four priority sectors due to its “quantity of PFAS in use and the variety of uses.” The report states that “more than 8,000 chemical substances are potentially used in the textile industry,” which grew from $381 billion in 2000 to $719 billion in 2017 and is predicted to continue to grow in the next 10 years.

The report indicates that “a significant portion of PFAS in manufacturing waste streams are released into industrial wastewater treatment plants,” which it says cannot adequately capture PFAS.

As public awareness about the health risks of PFAS grows, so too does public demand for action. For example, the NRDC report said that Greenpeace’s Detox My Fashion campaign resulted in more than 7,000 people in 80 cities in 20 countries protesting at Zara stores and headquarters demanding toxic-free fashion. The fashion retailer’s parent company, Inditex, responded by vowing to eliminate hazardous chemicals from its life cycle and production by Jan. 1, 2020. Inditex now links purchasing decisions to suppliers’ environmental performance.

Consumer demands for toxic-free products are only expected to grow in the marketplace and in U.S. statehouses and Congress, as well the EU and other regions.

Stricter U.S. regulation is expected

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is expected to classify perfluorooctanoic (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), two of the most common PFAS compounds, as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), a.k.a Superfund, by 2023, which would create “cradle-to-grave” requirements of the compounds. The EPA also has the authority to regulate PFAS through the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA).

In addition, more than 50 bills to address PFAS have been introduced in Congress between 2021 and 2022, according to policy consulting group Global Counsel. As of May, 20 states have issued widely ranging PFAS standards or regulations for drinking water, with California having the smallest allowable concentration of 5.1 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA only and Nevada having the largest with 667,000,000 ppt for perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) only, according to the JD Supra website. More state and federal regulations are expected.

PFAS litigation is on the rise

Another risk for companies is lawsuits related to PFAS pollution. More than 6,400 PFAS-related lawsuits have been filed in federal courts between July 2005 and March 2022, according to Bloomberg Law.

And the cost of such lawsuits is consequential. For example, it cost DuPont, Chemours, and Corteva $4 billion for PFAS-related liabilities and it cost 3M $850 million to settle with the state of Minnesota over PFAS contamination of drinking water and natural resources in the Twin Cities metropolitan area.

Michael Blumenthal, an attorney with McGlinchey Stafford PLLC, said to Bloomberg Law that if PFOA and PFOS are classified as hazardous waste, “landfills will have no choice but to go after industries that contributed the chemicals.”

“There will be so much litigation,” he added.

Current PFAS management falls short

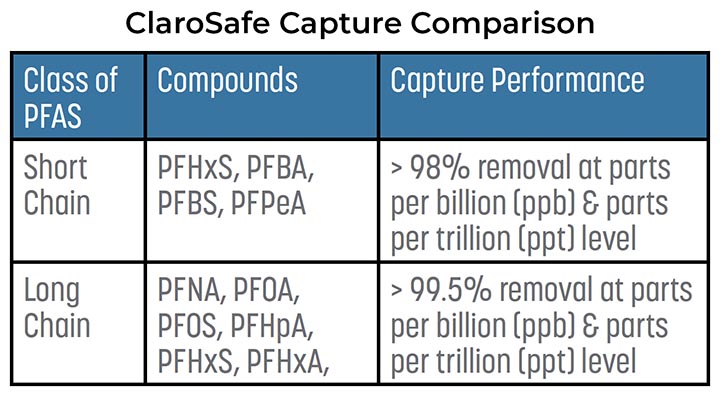

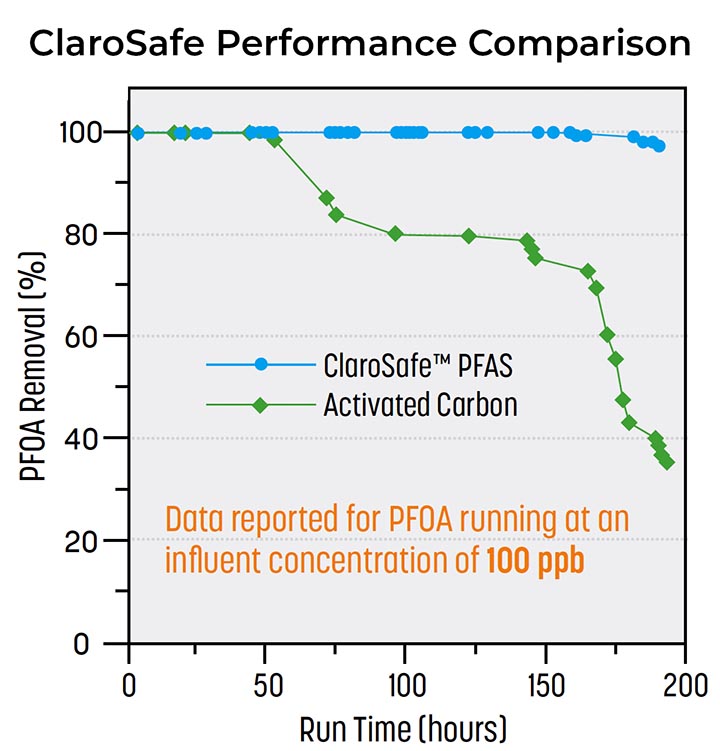

The most common practices for PFAS management are reverse osmosis, ion resins, or granulated activated carbon to filter PFAS from wastewater streams. A major problem with current PFAS filtration is, as the NRDC reports, “that widely used treatment technologies for the removal of PFOA and PFOS from water, such as granulated activated carbon, become progressively less effective for removing shorter chain PFAS as the chain length diminishes.” And short-chain PFAS molecules do not seem to be any less toxic than long-chain PFAS. C&EN reported that the U.S. National Toxicology Program found higher doses of short-chain PFAS have the same harmful health effects as their long-chain counterparts.

Filters laden with PFAS are then sent to landfills, which contaminates soils, or incinerated, which contaminates air and soil. One of the most common disposal methods, incineration breaks down long-chain PFAS into small-chain PFAS that are quickly spread by ash and smoke. The U.S. Department of Defense recently banned incineration of PFAS materials and there are many efforts afoot worldwide that seek to do the same.

In addition to the recontamination issue, both landfill and incineration disposal methods for PFAS are becoming too expensive to make sense for many industries, especially since the originator of the waste may still hold significant liability risk in the future.

Case Study

While quick to point out the risks and liabilities of the EPA designating PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances, Global Counsel also pointed out that “tailwinds abound for companies monitoring and remediating PFAS chemicals, and chemical manufacturers developing PFAS-free products.”

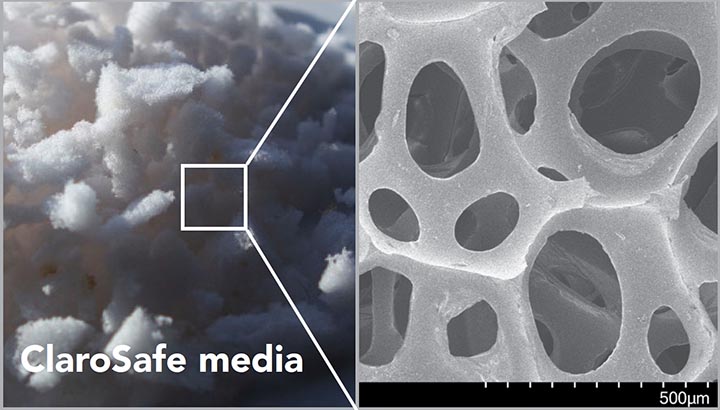

New technologies hold the promise of destroying PFAS, taking the “forever” out of “forever chemicals.” As an example of a method of such technology, Claros Technologies, a chemical engineering company, provides an end-of-life solution for PFAS. The company’s sorbent product captures PFOS and PFOA, a process that concentrates them, and a defluorination treatment that breaks their powerful chemical bonds.

“We designed a system that protects the planet and profits,” said Dr. John Brockgreitens, research and development director for Claros. “Our ClaroSafe™ PFAS system, which effectively destroys PFAS, is highly adoptable, adaptable, and cost-effective for many types of facilities. We have removed barriers to PFAS remediation.”

The first step in the ClaroSafe™ PFAS system is capturing all PFAS pollutants – not just those that are currently regulated. That means companies would remain in compliance with expected future regulations. Brockgreitens enumerated the five key ways the ClaroSafe™ PFAS filtration system differs from granulated activated carbon:

- Facilitates flow rates that are five times faster

- Captures short- and long-chain PFAS and other pollutants

- Has a loading capacity that is 30 times higher

- Requires less space since it’s 40% smaller

- Has seven times the longevity, requiring fewer filter changes and disposal

The second step concentrates PFAS waste by more than 100,000 times, making it easier to manage and destroy, Brockgreitens said. Lastly, the concentrated PFAS waste is put in the Elemental™, a PFAS-destruction mechanism that permanently breaks the powerful carbon-fluorine bond, he said, leaving behind only safe, naturally occurring elements.

“The ClaroSafe™ PFAS system reduces production slowdowns and bypasses thorny disposal issues,” Brockgreitens said. “And the system is customized for each facility so there is no need for costly retrofitting.”

Claros announced in May a multimillion-dollar partnership with Kureha Corp. of Japan to install the ClaroSafe™ system for its Asian markets. Kureha manufactures specialty chemicals and plastics, agrochemicals, and pharmaceuticals.

“As a chemical company, Kureha has responsibility for mitigating the environmental impact of PFAS,” said Naomitsu Nishihata, president of Kureha America. “We seek to be socially responsible, accelerate innovation, and expand our business portfolio. And Claros’ comprehensive PFAS solution helps us meet each of those goals.”

Dr. Abdennour Abbas, Claros founder and CTO said of ClaroSafe™: “Our approach is to concentrate PFAS from millions of gallons of wastewater into a few gallons of PFAS concentrate that can be cost-effectively and permanently destroyed in a traceable fashion. It works on a variety of industry wastewater and even on firefighting foam. Changing the way we treat our chemical waste by adopting a closed-loop system will not only reduce risks for the public and the environment but also eliminate latent and future liabilities for manufacturers and waste disposal companies.”