New California Wipes Study Proves Flushable Wipes Work as Described; There is Yet Much Work to Do on Consumer Education for the Wipes Marketplace

In the fall of 2023, INDA, Association of the Nonwoven Fabrics Industry, joined forces with CASA, the California Association of Sanitation Agencies, and RFA, the Responsible Flushing Alliance to conduct a practical study on wipes flushability, in response to a directive from the 2021 Wet Wipes Labelling Law AB 818. The goal was to see what Californians are really flushing in order to help inform the consumer education campaign. A result of the study was seeing what kind of non-flushable wipes are being flushed, as well as the success of flushable wipes disintegrating as intended. An engineering firm was hired, and the team spent over two weeks at the Inland Empire Utilities Agency in Southern California and Central San in Contra Costa County in Northern California, analyzing material pulled from the waste stream. Here are details on the process and results.

International Fiber Journal: How did the flushability study originate?

Lara Wyss: The wipes industry has conducted other collection studies in different parts of the U.S., as well as there’s one that I’m aware of in London. In California, the 2021 Wet Wipes Labelling Law AB 818 requires that a collection study is conducted. What was different about this one was that it was a true partnership between CASA, the California Association of Sanitation Agencies, INDA, Association of the Nonwoven Fabrics Industry, and RFA, the Responsible Flushing Alliance, all who worked together to conduct this survey. We hired an independent water engineering firm, Kennedy Jenks, to help with the study structure – to facilitate and complete the reporting.

As a partnership of wastewater and industry working together, along with an independent engineering firm, we believed the results could be very, very accurate, for the wastewater and the wipes manufacturing industry to view as very credible. Also, members of INDA’s Technical Committee and representatives from INDA member companies participated to make ensure technically correctness.

The collection study took place in the Inland Empire, in Southern California and in Contra Costa County in Northern California, allowing us to compare results over these two different geographies.

Matt O’Sickey: The California collections study had characteristics of the other collections studies that we’ve seen in the past. Some of the characterization of the different categories and materials that we found were consistent with those other studies. We did that intentionally so that we could maintain the ability to compare back. Then, if there’s progress being made, we could show it; if there’s not progress being made, we could also show that.

IFJ: What did you know going into the study?

Wyss: California’s labeling laws and associated consumer education mandates requires us to do consumer surveys. What we found is that people are fairly aware of the “Do Not Flush” symbol that they’ve seen on products. However, 60% of people in California self-reported that they have flushed something that they knew was not flushable over the last 12 months. So that gives us definite area of opportunity to continue to educate people on why they shouldn’t be doing this.

Also, 26% of Californians falsely believe baby wipes are flushable, 18% for makeup removal wipes, and 70% for cleaning wipes. The good news is that 93% of consumers felt it was either somewhat or very important for their local communities to follow smart flushing habits. The flushability study revealed if what people are really flushing aligned with what they say they believe.

IFJ: How was the study structured?

Wyss: We collected 1,745 samples over four days – two days in northern CA and two days in southern CA. We also collected the items during peak flow time so that it could be a good, indicative sample.

O’Sickey: Before going to California, we assembled about 160 different samples of wipes that we bought from retail stores, such as big-box retailers Sam’s Club and Costco, popular stores Walmart and Target, and the Safeway and Kroger chains, representing the largest two grocery chains in California. We also shopped at the Dollar Stores, and the biggest drugstores, CVS and Walgreens, and Amazon.

We collected all types of bathroom-related wipes, including makeup removing, hemorrhoid, toileting, baby, cleaning, and disinfecting categories. We shopped Amazon for more unusual wipes. These samples represented more than more than 80% of what is available. We created comprehensive sample books in large binders to compare collected materials and categorize what Californians are flushing.

Wyss: In our waste collections, it is important to note that we were sorting by type, not brand. We also made sure all categories were included, including flushable wipes, which were not mandated to be included as a part of this study. We thought it was important to look at what other studies conducted in the U.S. included, as well as other things like paper towels, feminine hygiene, trash wrappers, and PPE. It was really a comprehensive study.

IFJ: How did you recover from the waste stream?

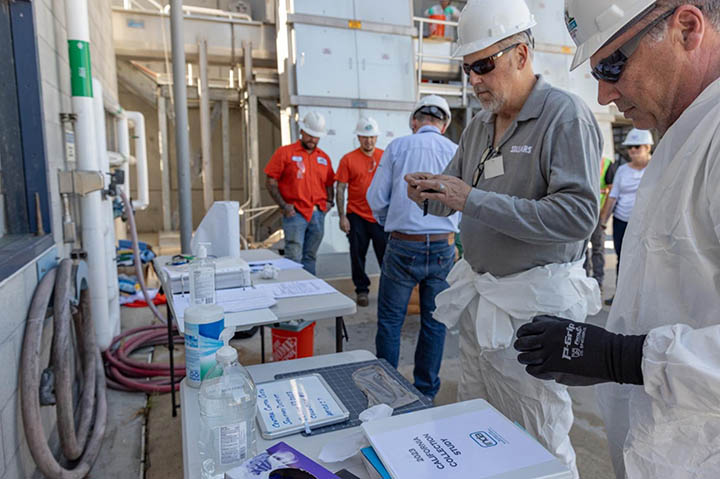

O’Sickey: There is a device that prevents certain materials from going past a point in the treatment plant. From this location, we recovered samples from the sewage material drawn up by a bucket. We were looking for things that were larger than one-inch square. We rinsed them, and then sorted the materials into categories. In many cases, it was easy to identify the samples from brand names printed on them, or in the case of baby wipes, from distinctive woven patterns.

IFJ: Describe the sorting process.

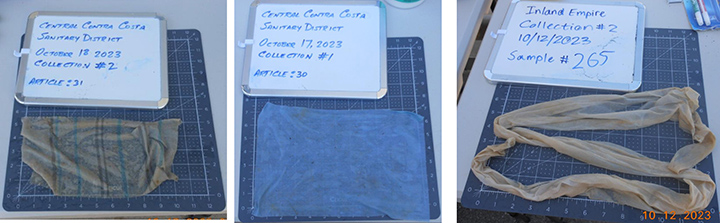

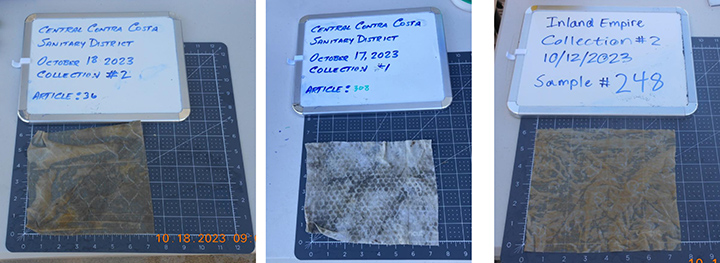

O’Sickey: Generally speaking, we found that there were a lot of paper towel products that came through entirely intact, feminine hygiene products and other trash that had to be sorted out. We laid all the wipes and related items out on a grid with pre-printed one-inch squares to get an idea of the objects’ dimensions, and to match them to the store-bought samples in our binders for which we had noted the dimensions. When we needed to differentiate between some products, we could use size as a differentiator.

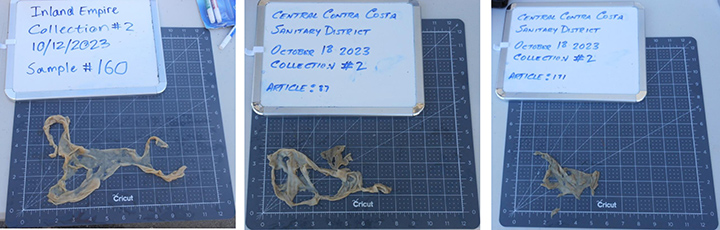

We recorded the category classification of each sample, we gave each a number, and took a picture of each one in order to do some post-investigation work.

We had three INDA members working to identifying items, and people from wastewater management and the CASA were there, as well. We had several INDA member company representatives who also provided help over the course of the two weeks that we were there. In many cases, due to their deep analysis of industry competitors, the industry guys knew exactly what the wipes were as they came out of the waste stream.

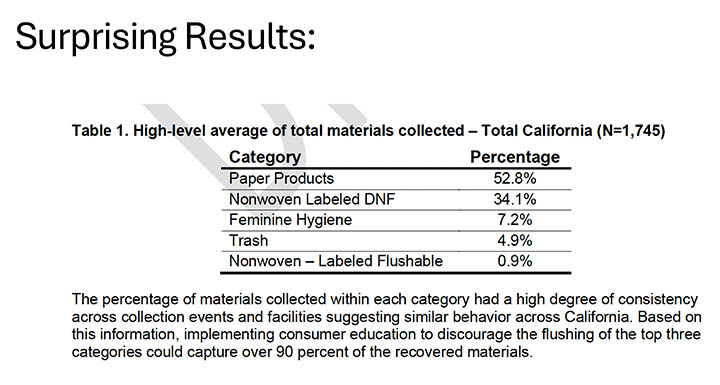

Then, we arranged them into category groupings, held down on tarps with a rock weight so they didn’t blow away. Interestingly, a majority of recovered items were actually paper towels and baby wipes. Everything else very quickly dropped off in number. The number one non-flushable nonwoven offender being flushed was baby wipes. If we could prevent that, we would be in much better shape, waste-wise. We’ve heard anecdotally that baby wipes are flushed frequently because they a cheaper alternative to adult incontinence-style wipe. (See Table 1 for specific results of materials recovered.)

Wyss: An eye opening for the wastewater team, recovery of flushable wipes was just under 1%. One operator at Inland Empire said, “I literally thought that we were going to find 99% flushable wipes.”

O’Sickey: As things came through, they’d see the paper towels, and assumed that those were actually wipes. So that also was a surprising misconception.

For our overall reporting, we indicated the date and place of collection and article number, from which we created a database of the 1,745 materials collected.

Wyss: As a non-technical person, I thought it was fascinating that everything that we collected was intact, except for the flushable wipes. From the paper towels to banana peels, toys, feminine hygiene, everything that came through was mostly or partially intact, except for the flushable wipes. For me, that was really illuminating.

O’Sickey: The very small number of flushable wipes we were able to retrieve were pretty much looking like Swiss cheese. Flushable wipes are designed to disperse with agitation in water. The flushable wipes that we did find oftentimes were stuck to something else, like a paper towel, another wipe, or some type of plastic wrapper, etc. They basically needed something to carry them along to get them to remain even partially intact enough to arrive at the collection point, which was interesting.

Wyss: Flushable wipes are made with very short fibers, whereas the non-flushable wipes are made with longer fibers and could also be synthetic fibers. Flushable wipes must always be natural fibers, such as plant based.

IFJ: If you didn’t find many flushable wipes, they are doing what they say by dispersing in water. Do you know how many are produced?

O’Sickey: INDA members know what the Nielsen data is for the number of flushable wipes that are being sold, but data that is carefully controlled. What we do know is that of all the wet wipes sold today, somewhere between called 8 to 12-13% are designed to be flushable, (percentage is based on which of the three ways you use to count them).

Out of the number of materials collected, in theory there would have been more than the 15 pieces of flushable wipes.

If they weren’t breaking down, there should have been somewhere in the range of 75-80 wipes.

IFJ: How will this data help the state of California with its wipes measures?

O’Sickey: From the nonwovens industry point of view, the test methodologies that companies use to determine flushablility in wipes – and there’s three or four different standards that are used – any given one of them must be working, because we just aren’t recovering anything that’s intact from wastewater streams. They all are effective in generating wipes that are going to disperse and disintegrate.

Wyss: From RFA’s perspective, it gives us some excellent data points to consider in our consumer education campaign. Our “Flush Smart” campaign is in year three. Our approach is to educate consumers to look for the “Do Not Flush” symbol on packaging, explain why that’s important, and to highlight, from a holistic approach, items beyond wipes that are should not be flushed.

This study really verified that this is the right approach. There is a real need to educate people to look for the “Do Not Flush” symbol on non-flushable wipes, especially if that’s roughly 90% of wipes sold in the U.S.

And then we must also remind them not to flush feminine hygiene products and paper towels. And one of the things that we’re focusing on this year in our campaign is “crimes of flushing.” We have a “toilet crimes” campaign we are unveiling during “flush smart” month, which is in July. We’ll be sharing more details about the campaign when we’re at WOW – World of Wipes, in June. It may involve a talking toilet, it may invite the public to share their flushing crimes. That’s the problem – toilet crimes – and the solution is “potty training for grownups.” We feel that these catchy marketing campaigns are something that will help us break through the information clutter coming at consumers 24/7 and grab their attention in a fun and unique way.

We are working through media relations with reporters about what we’re doing and sharing the messages of the importance of this issue – from a financial standpoint of clogging your own toilet all the way to a public health issue and environmental wastewater perspective.

I think the EPA says there’s between 23,000 and 75,000 sewage overflows a year, and an estimated that three and a half million people get sick from contaminated water.

We discovered from our consumer surveys that people agree it is very important to flush the right items for their own health and for the wellbeing of the community. We need to ensure that people understand the consequence of overflows or equipment failures at their Sanitation District results in consumer rate hikes.

This collection study confirms the need to explain why you don’t flush a baby wipe, and how it’s different from a moist flushable toilet tissue. They’re engineered different, they use different materials, the fiber lengths are different. And to emphasize, if you want to use baby wipes as a substitute because of cost, just throw it in the trash, do not put it down the toilet.

IFJ: Will legislative actions effect change?

O’Sickey: We are tracking at least 25 different bills or initiatives at the state, federal, and, in some cases, even the municipal level. They range from an action we are tracking in the UK proposing that all wet-wipes must use non-plastic materials to various labelling and disposal initiatives. In the USA, many of these diverse legislative initiatives will be consolidated and/or superseded by the WIPPES Act working its way now through Congress.

IFJ: Do you think there will be limits put on wipes production?

O’Sickey: Overall, nonwoven production and consumption in the U.S. has gone up reliably year after year after year. If we look at that pie, so the pie itself is getting bigger. If we look at the past five years, the slice of that pie that’s represented by wipes has also grown. So, growing pie, growing slice also. There is very strong consumer pull for wet wipes.

The question is, what happened? We used a lot of disinfecting wipes during COVID. Many consumers who, prior to 2020, were not wipes users were introduced to the category and it normalized their uses. The bottom line: they’re not going away.

Wyss: What I’ve noticed from attending the INDA nonwovens conferences, there is more discussion around making more sustainable fibers and solutions. So, I think that that’s positive sign for the future.

But, if you use an all-natural fiber in a wipe, that does not mean it’s flushable. And if it’s biodegradable, that does not mean it’s flushable. So, there’s a lot of nuances, and a lot of a lot of education that needs to be and can be done.