Fibers and textiles date back to the beginning of civilization itself, yet remarkably, the fundamental properties of these materials have remained largely unchanged for millennia. By and large, natural fibers such as cotton and wool, and synthetic fibers such as nylon and polyester form the foundation for the vast majority of textile products, yet functionally, these materials are relatively simple.

As such, humans continue to expect traditional features from their textile-based products, primarily used for protection, aesthetic, and cultural purposes. In the early 2000s, a fundamental shift in fiber technology occurred – a new class of fibers were invented, dubbed multi-material fibers[1]. Invented by MIT scientists in 2000, and subsequently spread throughout laboratories across the world over the past couple of decades, this new class of fibers enables the integration of disparate materials, including semiconductors, metals and insulators within a fiber form factor.

The ability to broaden the scope of materials processable into fibers has given rise to drastically new fiber functionalities, including fibers that can sense and actuate, store energy, change color, emit and detect light, store data, communicate, and more[1-6]. As a result, new textile-based applications emerged with increasingly sophisticated functions, such as fabrics with embedded sensors for healthcare, climate-adaptive textiles for self-regulated cooling, soft fabric light emitting displays and more.

This article provides a high-level summary of the foundational multi-material fiber technology and manufacturing methodology, the integration of these novel fibers into textiles, and an overview of some of the emerging applications. The work reported on here is primarily carried out by Advanced Functional Fabrics of America (AFFOA) is part of the Manufacturing USA Network, a collection of over 150 organizations working to advance the manufacturability and commercialization of functional fibers and fabrics in the US.

Preform To Fiber Draw Manufacturing Process

Traditional approaches to synthetic fiber manufacturing, such as melt spinning, are not conducive to manufacturing fibers comprised of disparate classes of materials. While a wide range of polymers can be readily extruded with melt spinning, the low viscosity processing of the material makes for integration of different materials classes a significant challenge. As such, an entirely different processing methodology was developed to manufacture multi-material fibers.

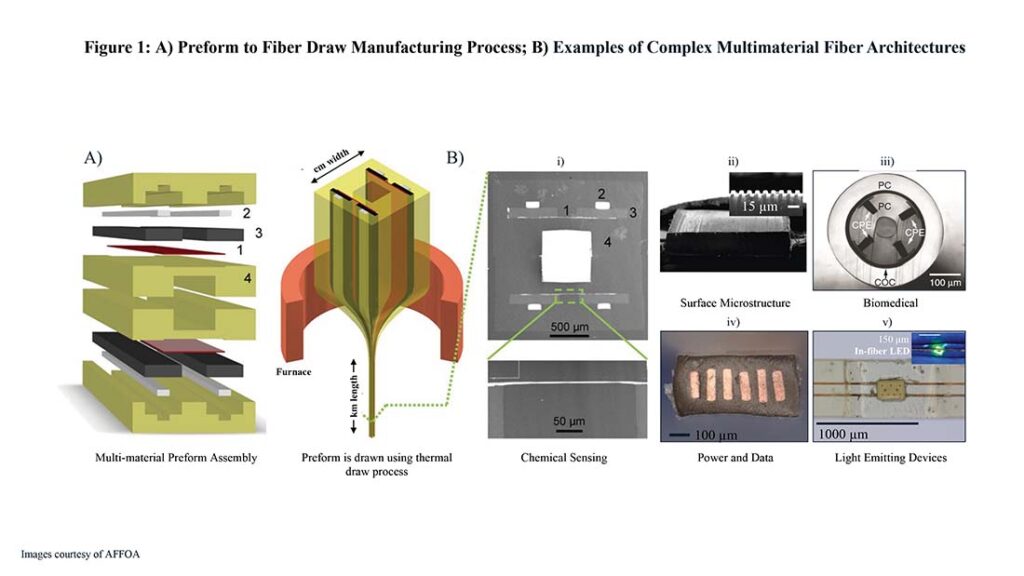

The foundation of the methodology is Preform-to-Fiber drawing – the same basic technique that is used to produce the glass telecommunication fibers that span the globe and enable world-wide communications. Unlike the traditional preform-to-fiber drawing, which involves the thermal drawing a single material (typically glass or polymer), multi-material fiber drawing involves constructing multi-

material preforms.

These preforms comprise all the materials of the final fiber, arranged in specific and controlled geometries. The multi-material preform is heated in a furnace and drawn into a fiber hundreds of meters or even kilometers long. Because the thermal preform-to-fiber draw process is performed in a high viscosity state, the cross-section of the preform can be maintained down to the fiber level.

Figure 1 illustrates the preform-to-fiber draw methodology along with several representative fiber cross sections. Interesting to point out are that non-equilibrium cross sections, such as rectangular features, can be obtained with this manufacturing process.

Microelectronics in Fibers

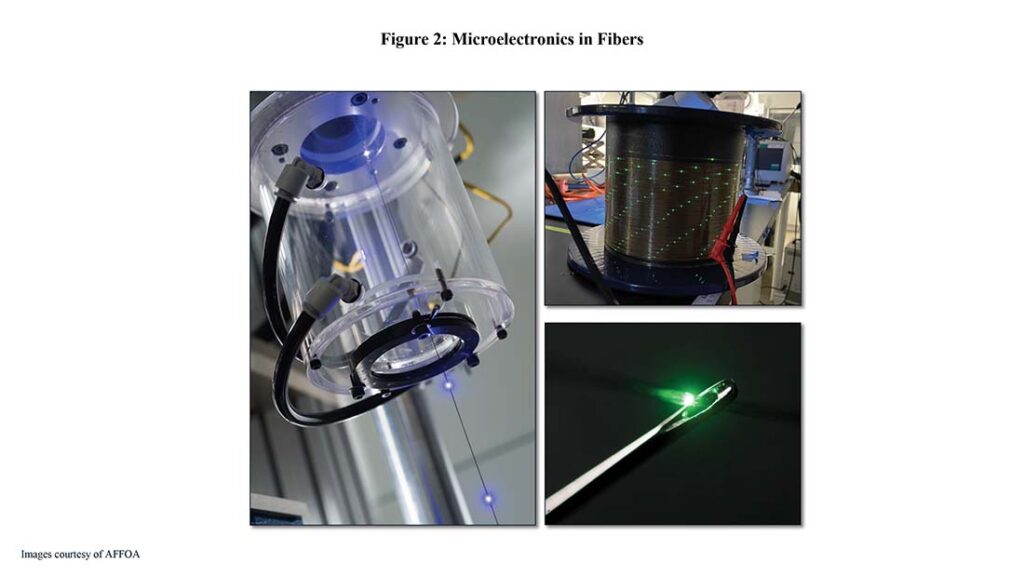

A unique modification of the preform-to-fiber draw process can be implemented to draw materials into fibers that themselves do not change viscosity during the draw process. This approach is employed when aiming to introduce conventional microelectronic components from materials such as Silicon, that melt at temperatures exceeding the polymer-clad fiber draw temperatures.

To accomplish this, the microelectronic chips are introduced into the preform and a pair of hollow channels flanking the chips run the length of the preform. As the preform is drawn, metal wire (such as copper) is introduced into the channels. As the preform is drawn down into a fiber, the wires make electrical contact with the microelectronic chips and power supplied to these wires enables the electrical activation of the microelectronic chips within the fiber. A photo of the fiber coming out of the draw tower furnace is shown in Figure 2, where a fiber containing blue LED chips is being drawn. The spacing of these LEDs within the fiber is roughly 30 cm. Spools containing hundreds of meters of this fiber are drawn from a single preform. The fiber can be designed to contain a wide range of devices including LEDs, photodetectors, thermistors, RFIDs, and many more. Present work focuses on custom-designed chips that can be embedded in the fiber with increasingly sophisticated computation functionality.

Textile Integration

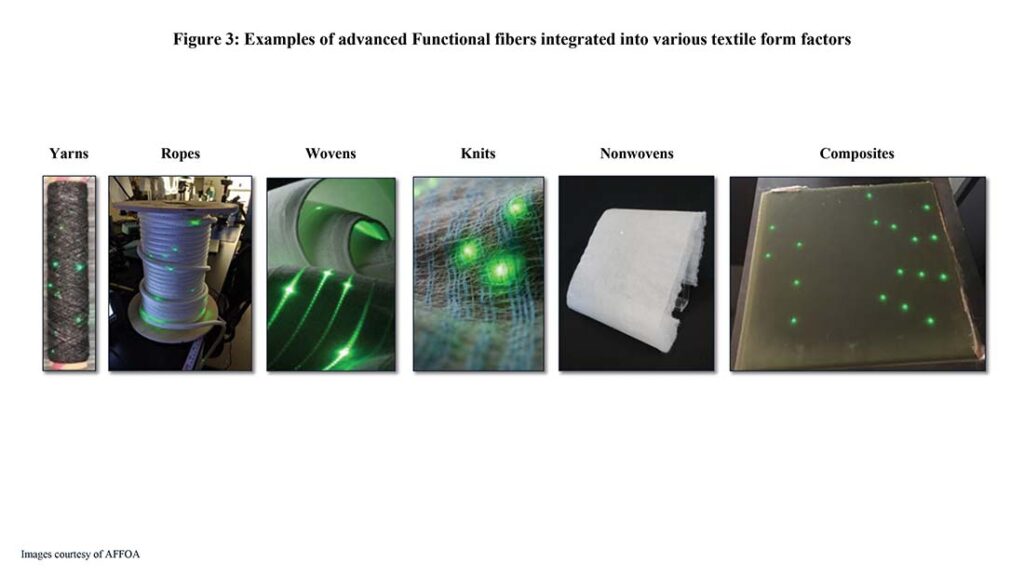

Advances in the preform-drawn chip-in-fiber technology now make it possible to construct textile-based electronic systems, where the electronic functionality is not added within a hard puck, but rather within the fiber itself. Working with AFFOA’s Fabric Innovation Network, the capability of these thermally drawn fibers to be introduced into a variety of textile production processes has been demonstrated.

Figure 3 shows how these advanced functional fibers, in this case fibers containing LEDs, can be embedded using a range of yarn and textile manufacturing processes. Over the past several years,

significant progress has been made on the reliability of these functional fibers and fabrics with rigorous bend, elongation, and wash testing demonstrating potential applications of this technology to real-life textile use cases.

Applications

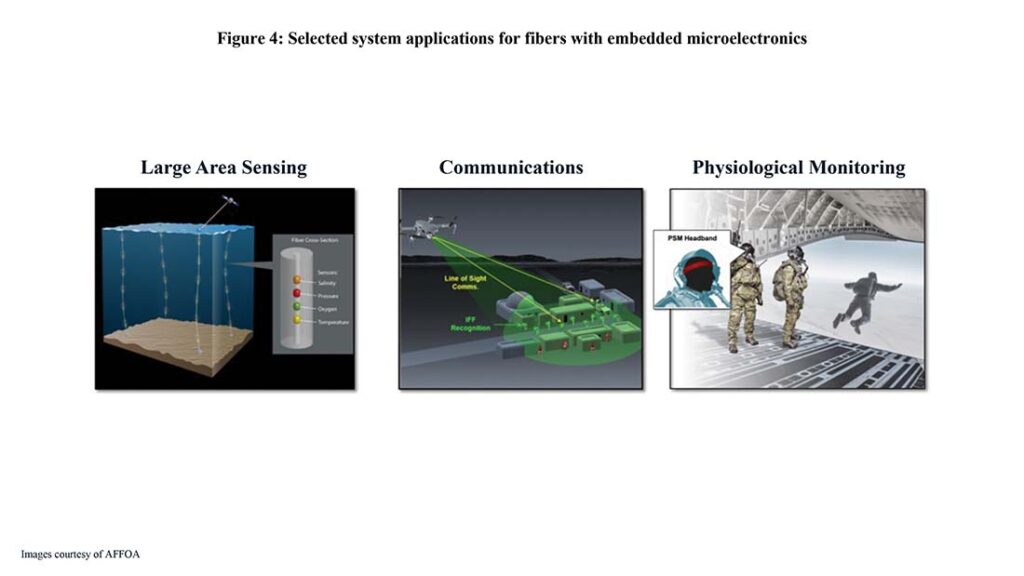

Advanced fibers with microelectronics are enabling radically new applications owing to the unique nature of this technology. For example, jointly with our partners at MIT Lincoln Laboratory, AFFOA is advancing fiber and fabric systems motivated by national security needs. Three classes of applications are discussed below, as depicted in Figure 4, which demonstrate just a few examples of the broad range of capabilities enabled by multi-material fibers.

Large Area Undersea Sensing: Given the length of these fibers and the ability to introduce semiconductor chips along their axis, the opportunity for large area distributed sensing becomes possible. One example where this technology is paving the way towards a revolutionary capability for the Department of Defense is in the area of undersea sensing. Large area oceanographic data is critical for planning and executing undersea missions from the tactical to strategic levels in the maritime domain.

However, today’s technologies for collecting oceanographic data often suffer from limited sensor modalities, long profiling times, data latency, and deployment system limitations. AFFOA, jointly with MIT Lincoln Laboratory, is developing a novel undersea sensing system and measurement scheme that addresses many of these shortcomings. Guided by US Navy mission needs, this system is comprised of a thin (mm-diameter) and long (hundreds of meters) fiber with embedded sensors positioned along the

fiber axis at meter-class spacing. A single electrical connection at one end of the fiber is used to individually address and read data from hundreds of sensor nodes along the fiber (Figure 4, Left).

Key to this system is its ability to continuously record profiles of multiple oceanographic parameters versus depth and report them in real time – a potentially crucial advantage over existing, point measurement-based profiling systems. Temperature profiling over a 100-m long fiber was recently demonstrated in the ocean, with other sensing modalities (salinity, optical, magnetometry) currently

in development. This work paves the way for a multi-modal persistent oceanographic data measurement system tailorable for mission-specific air, surface and sub-surface deployment, offering critical sensor support not available with today’s technologies.

Communications: Secure communication on the battlefield is of critical importance, especially in urban settings where probability of intercept and detection by enemy forces is high. While conventional radio-based communication schemes continue to be predominantly employed, their susceptibility to jamming and/or interception is a limitation.

An alternative communication scheme uses light to transmit data. Unlike radio frequency waves, light can be directional (e.g., sent over a laser), thereby greatly reducing the probability of intercept or detection. By embedding light detecting and light emitting fibers into the fabric of a soldier’s uniform, the fabric itself becomes a communication system – it can receive and transmit optical data. AFFOA in collaboration with MIT Lincoln Laboratory has demonstrated several fabric-based light communications systems using this approach. Specific use-cases range from improved identification of friend versus foe schemes (Figure 4, Center) to soldier-to-soldier communications.

Physiological Status Monitoring: Continuous, real-time physiological status monitoring (PSM) for early detection of acute hypoxia, enabling action prior to impairment or injury, is a mission-critical system need for High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) jumpers (Figure 4, Right).

Existing technologies to address this need are insufficient due to inaccuracies and user-friction associated with conventional wrist-worn PSM wearables. Sponsored by the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine (USARIEM) and in partnership with end-users from the US Air Force Special Operations Command, AFFOA in collaboration with MIT Lincoln Laboratory has developed a fabric headband sensor system, enabling increased measurement accuracy.

The fabric contains embedded microelectronic components that measure key physiological status markers including temperature, heart rate, and blood-oxygen levels. Data is transmitted wirelessly from the fabric to a smartphone, with an edge-computing architecture supporting over 40 hours of continuous battery life. Many headbands can communicate to a single smartphone, enabling the mission commander or medic rapid access to the readiness status of multiple jumpers in real-time. This system has undergone initial end-user testing in a simulated high-altitude environment and has successfully demonstrated the ability to identify moments of induced hypoxia. Feedback from these tests is informing improvements to fit that will be included in future development efforts.

Next Generation Functional Fiber

Multi-material fibers drawn from a preform are enabling a new class of functional fiber and fabric systems. AFFOA and its Fabric Innovation Network are working to bring these new technologies to market with pull from both the Department of Defense and commercial industry. AFFOA has the internal subject matter expertise and equipment to prototype new multi-material fiber architectures as well as scale-up existing fiber technologies and is always looking for new applications and opportunities to collaborate with domestic partners to bring them to market.

AFFOA is a non-profit, public-private partnership founded in 2016 as one of the nine DoD Manufacturing USA Innovation Institutes. Headquartered in Cambridge, MA, AFFOA’s mission is to rekindle the domestic textiles industry by leading a nationwide enterprise for advanced fiber & fabric technology and manufacturing innovation, enabling revolutionary new system capabilities for commercial and defense applications.

To catalyze the development of advanced functional fibers and strengthen the domestic textile industrial base, AFFOA has assembled a Fabric Innovation Network (FIN) made up of 150+ member organizations including startups, universities, manufacturers, commercial industry and defense partners to bring advanced fiber technologies to market.

The reader is encouraged to contact AFFOA to learn more about collaboration opportunities and support for your organization’s research and development objectives.

References

1. Abouraddy, A. F., Bayindir, M., Benoit, G., Hart, S. D., Kuriki, K., Orf, N., Shapira, O., Sorin, F., Temelkuran, B., Fink, Y., “Towards Multimaterial Multifunctional Fibres that See, Hear, Sense and Communicate,” (invited review paper) Nature Materials 6, No. 5, 336-347, May 2007.

2. Loke, G., Yan, W., Khudiyev, T., Noel, G., & Fink, Y. (2019). Recent Progress and Perspectives of Thermally Drawn Multimaterial Fiber Electronics. Advanced Materials, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201904911

3. Gumennik, A., Stolyarov, A.M., Schell, B.R.*, Hou, C., Lestoquoy, G., Sorin, F., McDaniel, W., Rose, A., Joannopoulos, J.D., Fink, Y., (2012) “All-in-fiber chemical sensing,” Advanced Materials, DOI:10.1002/adma.201203053

4. Khudiyev, T., Hou, C., Stolyarov, A.M., Fink, Y. (2017) “Sub‐Micrometer Surface‐Patterned Ribbon Fibers and Textiles,” Advanced Materials, DOI: 10.1002/adma.201605868

5. Canales, A., Jia, X., Froriep, U.P., Koppes, R.A., Tringides, C.M., Selvidge, J., Lu, C., Hou, C., Wei, L., Fink, Y., Anikeeva, P. (2015) “Multifunctional fibers for simultaneous optical, electrical and chemical interrogation of neural circuits in vivo,” Nature Biotechnology, DOI:10.1038/nbt.3093

6. Rein M., Favrod V.D., Hou C., Khudiyev T., Stolyarov A., Cox J., Chung C.C., Chhav C., Ellis M., Joannopoulos J., Fink Y. (2018) “Diode fibers for fabric-based optical communications.“ Nature 560, 214-218. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0390-x