New legislative measures aimed at protecting the environment within the European Union are likely to make things extremely difficult for synthetic fiber producers in the coming years.

The European Green Deal will see €750 billion pumped into a wide range of projects with the overall aim of making the entire continent climate neutral by 2050.

In March 2020, as part of it, the European Commission introduced a new circular economy action plan aiming to stimulate the development of climate neutral and circular products. It will prioritize reducing and reusing materials before recycling them and set minimum requirements to prevent environmentally harmful products from being placed on the EU market. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) will also be strengthened and will focus, in particular, on resource-intensive sectors such as textiles.

Alongside this, are the Single-Use Products Directive, which as previously reported in IFJ, is putting pressure on the manufacturers of various nonwoven products to come up with alternative raw materials or face penalties, and the updated Waste Framework Directive, which will oblige member states to set up separate waste collections for textiles by January 2025.

Where all this textile waste will go – and who will pay for its collection, sorting, recycling or disposal – is yet to be finalized.

Used clothing

COVID-19 has not been kind to the used clothing and textiles industry, with the major markets in Africa, Pakistan and India all completely closed, either through the direct banning of imports, lockdown measures, or for other extraneous reasons.

This contraction of the markets has resulted in pressure on prices and competition between the U.S. and Europe. According to the latest data from UK site letsrecycle.com, the price per ton of used clothing from textile banks fell from £100-170 in January this year to £0-60 in May, although since June it has rallied slightly, to between £20-80.

Only a small percentage of all textile waste generated is in any case handled by the existing industry, and of the one hundred million tons of fibers produced every year, seventy million tons end up in landfilll.

Further, of the estimated 150 billion garments produced for the global fashion industry each year, 30% are sold at discounted prices and a further 30% never sold at all.

Recycling options

A special session on recycling held during the recent virtual Global Fiber Congress (Dornbirn-GFC) involved the machinery-building companies Erema and NGR Plastic Recycling Technologies of Austria, and Oerlikon, headquartered in Switzerland. All have fiber recycling technologies but they are each intended for dealing with pure fibers, textiles and plastic waste generated during the production processes.

While intensive research is ongoing into developing recycling options for post-consumer clothing, it was said at the conference that any successful solution that could be industrially scaled to deal with the problem – most likely involving chemical or enzymatic processes – was at least a decade away.

This view, however, may be overly pessimistic, since there are a number of very ambitious new projects now gaining traction.

Endless loop

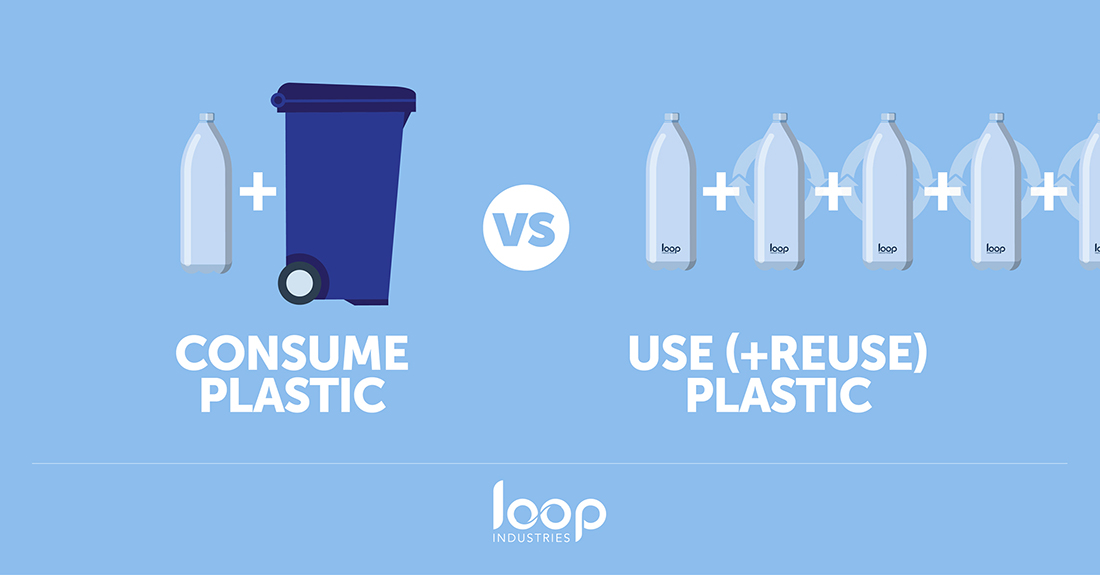

One of the world’s largest polyester manufacturers, for example, Thai-headquartered Indorama Ventures (IVL) – which among other things has pledged to recycle 50 billion PET bottles a year by 2025 – has an exclusive license to use the technology of Canadian company Loop Industries for PET polyester fiber production.

This technology allows plastics of no or little value to be recycled endlessly into new, virgin-quality PET. This includes plastic bottles and packaging of any color, transparency or condition, as well as carpet, clothing and other PET textiles that may contain colors, dyes or additives – and even plastics reclaimed from the sea that have been degraded by sun and salt.

Through Loop’s patented zero energy depolymerization technology, the waste plastic and fibers are completely broken down into their constituent monomers – dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and mono ethylene glycol (MEG). The monomers are then purified, removing all coloring, additives, and organic or inorganic impurities.

From there, the DMT and MEG components are repolymerized into new PET plastic.

In September this year, Loop announced a further agreement with Chemtex Global Corporation to license Invista’s plastic and PET polymer for fiber manufacturing know-how. Also in September, the company announced a plan to build the first “Infinite Loop” recycling facility in Europe with Paris-based environmental services company Suez.

Loop has also just raised $24 million in new funding from a common stock round.

Planned investments

As one of the largest manufacturers of polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE), LyondellBasell, headquartered in Rotterdam, meanwhile plans to produce and market two million metric tons of recycled and renewable-based polymers annually by 2030.

It aims to achieve this through planned investments in three central technologies – molecular recycling, mechanical recycling and polymers based on renewable feedstocks.

Molecular recycling

LyondellBasell says its molecular recycling technology, MoReTec, is on its way to becoming one of the solutions that can address the challenge of hard-to-recycle plastics such as multilayer and hybrid materials which can’t be easily recovered by mechanical recycling. It produces clean feedstock made from recycled materials for new polymer production.

The company has established a molecular recycling pilot plant in Ferrara, Italy, which is processing household plastic waste at a rate of five-to-10 kg an hour.

Mechanical recycling

To create high-quality recycled polymers from household waste with mechanical methods requires a careful selection of PP and PE materials from the waste stream, further treatment and color sorting.

LyondellBasell is also in a joint venture with Suez in a mechanical recycling facility called Quality Circular Polymers (QCP).

The QCP plant is currently capable of converting consumer waste into 35,000 tons of recycled PP (r-PP) and recycled high-density PE (r-HDPE) annually, with the objective of reaching 50,000 tons in 2021.

Renewable feedstocks

Working closely with Neste, a leading renewable raw material supplier based in Ispoo, Finland, LyondellBasell has already achieved the first parallel production of PP and low-density PE (LDPE) made from renewable raw materials at commercial scale.

It is offering a new range of polymers called Circulen and Circulen Plus made from renewable raw materials such as cooking and vegetable oil waste, as drop-in solutions delivering the same high-quality properties as virgin plastics.

“Overall, plastics have too much value to be thrown away, but the price of a single plastic component is so low it’s difficult to recapture any of that value,” Layman said. “Plastics are both a success and a tragedy, being so pervasive and useful in our lives, but not in the environment.“

PureCycle

Over in Ironton, Ohio, PureCycle Technologies (PCT) is planning to build a commercial plant for PP resins recycling capable of processing 50,000 tons annually within the next two years.

The company started up a pilot plant with an annual capacity of 70 tons in July 2019, at its base in Ohio and has just raised $250 million in a bond issue.

While PCT operates independently from Procter & Gamble, which invented the resin recycling process, it is likely to play a major role in helping the corporation meet ambitious goals. P&G intends to make all of its packaging recyclable or reusable – and to replace 50% of all of the virgin plastics it uses with recyclable or reusable alternatives – by 2030.

“How we achieve this 50% reduction will be via a number of routes, either by employing recycled or biobased materials,” said John Layman, Procter & Gamble’s head of corporate R&D and the founding inventor of PCT, at the recent 2020 INDA World of Wipes virtual conference. “Lightweighting is a further option but it’s an avenue we’ve already explored and made plenty of progress in.”

With sales of $71 billion in its financial year to June 2020, P&G is a huge user of PP, in nonwovens but also in injection molded components and plastic films.

Success and tragedy

“Overall, plastics have too much value to be thrown away, but the price of a single plastic component is so low it’s difficult to recapture any of that value,” Layman said. “Plastics are both a success and a tragedy, being so pervasive and useful in our lives, but not in the environment.

“There is a lot of lip service currently being given to circularity but there is not as much true recycling going on as consumers think. A single recycling step of turning waste plastic into park benches which then go to landfill is not enough – achieving quality that is just like virgin PP with the same regulatory approvals, and restoring it to products with no trade-offs in an endless cycle, is PCT’s goal,” said Layman.

The three main challenges, he added, are removing contamination, color, and malodor. “The plastics waste stream consists of a huge diversity of different plastics in different forms, so pulling a single polymer out of it profitably is extremely tricky,” he said.

Purification

PCT’s proprietary technology is based on using a hydrocarbon solvent at elevated temperatures and pressures, and a novel combination of standard chemical engineering operations. These processes purify the recycled resins via the removal of odor, volatile organic chemicals, and other organic and particulate contaminants and additives.

“It’s a polymer-to-polymer process, to feed dirty plastic in and clear plastic out,” Layman said. “The end product has the same mechanical properties as virgin PP with the same tensile modulus and impact strength.”

The energy consumption of the process is also impressive, requiring 23MJ per kg of product, including all logistics and transportation, compared to 70MJ per kg of virgin PP.

“A key advantage is the simplicity of PCT’s process, which requires a lot less steps than pyrolysis, consumes a lot less energy and ultimately is much more cost effective,” Layman concluded. “Our existing plant is sold out for the next twenty years and we have been pleasantly shocked at the amount of demand there is from the market.”

Willingness

These separate developments – while they may be a drop in the ocean in terms of addressing the huge problem of plastic waste – are reassuring in showing the fiber industry’s willingness to adapt and change, and to make funding available to do so. Many new initiatives can be expected, because the European Union is not alone in planning legislative measures.